Investor Behavior: Impact of Cognitive Bias

Written By: Brian Ellenbecker, CFP®, EA, CPWA®, CIMA®, CLTC®

As human beings, we all have cognitive biases. A cognitive bias is an error in thinking that occurs when we are processing and interpreting information in the world around us. It affects the decisions and judgements we make. Oftentimes, they are a result of the brain’s attempt to simplify information processing. Our brain creates rules of thumb to help us make sense of the world and reach decisions with relative speed. Unfortunately, the process of speeding up the decision process can sometimes lead to errors.

When it comes to investing, cognitive biases can make our investing behavior irrational. This can lead us to make undesirable financial or investment choices because we draw incorrect conclusions based on some of the thinking errors our brain is making to arrive at those decisions.

To be a successful investor over the long term, we need to understand, and hopefully overcome, some of these common cognitive biases. Doing so can lead to better decision making, which may help lower risk and improve investment returns over time.

Let’s look at some of the most common cognitive biases that can impact our investment decisions.

Anchoring Bias

Anchoring causes us to rely too heavily on the first piece of information we are given about a topic. When we are first introduced to the price of an investment, its current price has a lasting impact on our brains. Let’s look at Microsoft as an example:

- If you started following Microsoft in 1997, it first traded above $10 in January of that year.

- It currently trades at over $300 per share.

- However, it never broke the $100 barrier until the summer of 2018. In fact, during the tech run in the late 90s through early 2000, the stock only traded above $50 for a few days in late 1999 and early 2000. It had a sustained run in the $25-$35 range from post September 11, 2001, until late 2013.

- Once the stock hit $100, if you thought it was overvalued because it used to trade for $10 when you first started following it, you would have missed out on tripling your money!

The key takeaway is to evaluate an investment based on its future potential, not its past performance!

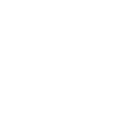

Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias occurs when you only seek out information that tells you what you want to hear. You seek out information that aligns with your opinions and ignore information that contradicts them. This can cause you to both make an investment that isn’t appropriate AND hold onto it longer than you should. While it can be difficult to admit your mistakes and move on, some of the most successful investors are willing to admit their mistakes and move on quickly.

Sunk Cost Bias

A person’s inability to move on from an investment can also be seen in their sunk cost bias. A sunk cost is a cost that has occurred and can’t be recovered. We tend to keep investing more money or over-committing because we’re scared of losing our original investment. Instead, you should evaluate an additional investment just like any other investment—should you be allocating new money to that existing investment or is there a better opportunity available? Don’t throw good money after bad.

Example:

You invested $25,000 in a friend’s restaurant. It is performing terribly. Your friend asks for another $5,000 to start “taco Tuesdays”. Are you tempted to invest more to try to “save” your initial $25,000?

Loss Aversion

Losing money feels worse than gaining money. Winning $100 does not feel the same as losing $100. Losing is painful. Your brain typically makes you feel 2.5 times worse when losing vs. the positive feelings you have when gaining.

If a stock you own is down 50%, you could sell the security and cut your losses. Loss aversion means some people will prefer to wait it out, as they’re afraid “locking in a loss” by selling. However, the money is already gone. You can still lose the remaining 50%, or 100% of its current value!

Loss aversion can also lead to unnecessary risk avoidance. People may vow to never invest in a losing deal again. While there are surely lessons to be learned from past experiences, it could also mean missing out on the returns you need to meet your financial goals. Weigh the risks vs. rewards properly.

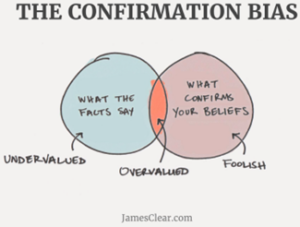

Recency Bias

Recency bias acknowledges that people tend to put too much emphasis on recent events, even if they are not the most relatable or reliable. It may lead investors to think that the current market downturn or rally will extend into the future. It can lead you to make short-term decisions that deviate from your long-term financial plan.

Recency bias can be hard to avoid and leads us to making irrational decisions, such as following a hot investment trend or selling securities during a market downturn. It’s particularly important to be aware of this bias. Sticking to your long term financial and investment plan is often the best way to combat it.

Overconfidence Bias

Overconfidence bias is the tendency for a person to overestimate their abilities. Whether it leads you to think you are a better-than-average driver (73% of Americans think they are above average drivers, according to a AAA survey) or an expert investor, overconfidence can lead to bad decisions. If you get lucky and pick the right investment a few times, you may end up thinking you’re a more skilled investor than you really are. This can lead to making increasingly more risky investments and ultimately lead to losses larger than you can tolerate.

Solid risk management strategies as a part of a disciplined investment process are the key to beating overconfidence.

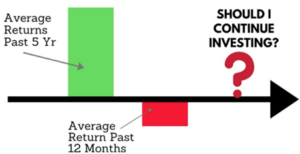

Endowment Effect

The endowment effect recognizes that people tend to irrationally put a greater value on something they own versus its actual market value. Oftentimes, someone become emotionally attached to what is “theirs”. We see this with real estate, personal property and investments.

To beat the endowment effect, ask yourself this question: “If I didn’t own the investment, would I invest in it today?”. Thinking about your investments this way helps keep your viewpoint more neutral.

Survivorship Bias

Survivorship bias occurs when only the winners are considered while the losers that have disappeared are not considered. This commonly occurs when evaluating mutual fund performance (where merged or defunct funds are not included) or market index performance (where stocks that have been dropped from the index for whatever reason are discarded). Survivorship bias skews the average results upward for the index or surviving funds, causing them to appear to perform better since underperformers have been overlooked.

When evaluating an investment, be sure the data you are looking at adjusts for survivorship bias. Ignoring it could lead you to an investment that is riskier than it appears on the surface or mislead you regarding an investment’s long-term track record and prospects.

Narrative Bias

People tend to interpret information as being part of a larger story or pattern, regardless of whether the facts actually support that narrative.

There are numerous examples of investments exploding in popularity because of their story, not necessarily because of their true long-term prospects. Think of these recent examples of narrative bias:

- Hundreds of new cryptocurrencies have been created with no immediate, discernable purpose other than having a catchy name or gimmicky story. People still invest because the sector is hot and the coin’s story sounds good.

- Meme stocks, like Game Stop, AMC, and Bed Bath & Beyond, gained cult-like followings and saw large returns for a short period of time. Investors saw it as an opportunity to “stick it to hedge funds” that held short positions in those companies, not because the companies had a bright future or strong fundamentals.

Herd Mentality Bias

People have a tendency to follow and copy what others are doing. This often occurs in the investment world, as well. Investors’ tendency to follow and copy what other investors are doing is very common. These decisions are largely influenced by emotion and instinct, rather than by their own independent analysis. This bias is commonly referred to as the “Fear of Missing Out” (FOMO).

Availability Heuristic

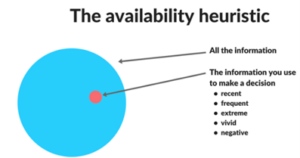

The availability heuristic describes someone’s tendency to use information that comes to mind quickly and easily when making decisions about the future.

When this tendency shows up while examining investment opportunities, it can lead to bad decision-making. These memories are usually insufficient for figuring out how likely things are to happen again in the future. All you are left with is low-quality information to form the basis of your decision.

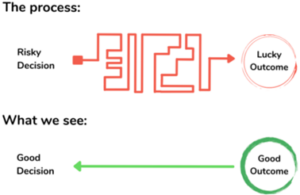

Outcome Bias

Outcome bias overemphasizes the result and deemphasizes the events preceding the outcome. People often judge entire processes by their outcomes and not by the quality of the process itself. This bias causes people to confuse luck with skill. Unfortunately, outcome bias is difficult to detect in our daily lives. In all but the most obvious cases, it’s hard to separate the quality of the process with the outcome resulting from the process.

Conversely, a bad outcome doesn’t always mean the process was bad. Sometimes the best laid plans don’t always produce the result we want in every case. That’s life! Base your decision on what has the best odds of success and you should achieve more good outcomes than bad over time.

In the investment world, it’s also very difficult to separate luck from skill. When the markets are going up, everyone feels like they are good investors. Over the past five years, it was hard to go wrong with making money on an investment, whether it was stocks, real estate, cryptocurrency, etc. There were far more winners (stories of 10x+ returns were not uncommon to hear) than losers. With the recent market correction, many of these highflyers are now down 50% – 75% or more, likely wiping out the gains for many.

When the markets were still rising, most of those investors felt an inflated sense of confidence in their skill, when it was more likely luck that resulted in most of those gains. A market correction often exposes those with underdeveloped or undisciplined investment strategies.

Authority Bias

Authority bias is a person’s tendency to follow the leader. Once we believe someone is an expert, we tend to trust everything they say. In many cases, following the advice of an expert is the smart thing to do, but not always.

“Experts” can still be wrong, and some even have ulterior motives. People follow investment analysts on news channels and websites with very mixed results. It is important to remember that investors have different time frames, objectives and risk tolerances. If you are a long-term investor saving for retirement, and you are following the advice of a day trader (short-term focused), your objectives are not in line and you likely won’t get the result you were expecting because of that disconnect.

Food for Thought: A top economist has been saying at the beginning of each year since 2009 that a recession is coming. If we end up experiencing a recession in 2022, was that “expert” right? Technically, the economist could argue they were right. However, the S&P 500 returned 343% from the beginning of 2009 through May 10, 2022. If you were avoiding stocks for fear of recession, you probably missed out on significant gains in the meantime.

Unit Bias or Price Bias

Unit bias can lead to a distortion when comparing the merits of two investments:

- The price of a stock is not an indicator of its investment merits. Don’t assess the relative value of a stock based on its share price.

- For example: just because the price of a stock is low ($5 per share, as an example), doesn’t mean it’s cheap (or expensive). Conversely, just because a stock has a relatively high price ($1,000 per share, as an example), doesn’t mean it’s expensive.

- People tend to prefer to buy a “whole unit” of something, rather than a fraction of it.

- Consider this example: One Bitcoin might cost you $45,000, however, it’s easy to buy a fractional interest in a coin. They have the same relative value; however, we might perceive owning a whole coin as superior to owning a fraction of a coin. This is a common reason that people have bought coins that cost less per unit but may be an inferior investment.

- Always consider the market cap of the investment (price multiplied by outstanding shares), along with its future outlook and expectations. Looking at the entire picture will provide you with a better analysis of whether an investment is a good buy or sell at a given price.

Conclusion

We run into behavioral biases on a daily basis in many phases of our lives, including investments and finances. Acknowledging those biases even exist can be a great first step in not falling victim to making a bad decision because of them.

To help manage your biases, keep these tips in mind:

- Manage emotions.

- Seek contrary opinions.

- Avoid developing an unhealthy attachment to a particular investment. Great companies are not always great stocks, and vice versa.

- Don’t chase yesterday’s winners. There’s a reason most investments are required to disclose that “past performance is not indicative of future results”.

- Be cautious when following the crowd.

- Pay more attention to detailed analysis rather than to stories.

Your Shakespeare advisor can also help you navigate these biases to avoid making a bad decision based on our human impulses. Having a plan in place and a disciplined process to stay the course is one of the best ways to navigate these issues. We make sure our clients have those things in place to give them the best chance to succeed.